An annoying paradox of deep learning

10 April 2023

I’m listening to the popular 2021 book Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World by David Epstein. I feel like I’ve somewhat outgrown these types of books (journalist-authored, story-based, pop social science), but I like the general idea and it was for sale on Apple. I’ve always been more of a generalist despite the common narrative in society (and my profession) that specialization is everything.

In Chapter 4, Epstein talks about what I would call “the annoying paradox of learning” which is essentially that the most meaningful learning we do is often slow and even frustrating. It involves taking risks, making mistakes, asking questions, and being confused. It’s a paradox because mistakes and confusion feel like the opposite of learning. It’s annoying because we wish it didn’t have to be that way. But when we try to speed things up to boost performance in the short term, it almost inevitably undercuts our learning. It’s why Jonathan Haidt in his book The Happiness Hypothesis: Finding Truth in Ancient Wisdom admonishes readers that they’re welcome to skip to the end and read the main ideas but it’s the journey of the book that will lead to deep understanding. [Haidt’s book, which I read in 2011 in Cambridge, is one of my all-time favorites.] The idea that deep learning is slow and hard harkens back to the crucial role of a “disorienting dilemma” in Transformative Learning Theory.

It also reminds me of my personal experience learning statistics in grad school. At GW, I took every statistics course I could fit into my schedule. The intro classes came with exercises and PDF instructions on what to input into SPSS and what we should get out after doing so. Essentially, we weren’t learning anything fundamental about the principles of statistics. We were learning how to follow a manual. It wasn’t until I took regression and then structural equation modeling and then item response theory –– when I had what I might have labeled “bad teachers” –– that I really began to learn the foundations of statistics. It was only when my friend Zach and I toiled in the basement of the Gelman Library in Foggy Bottom that the lights began to turn on. We would sit at adjacent computers (each with our coffee from the Starbucks above) and work on analyses independently, but together. We had endless moments of frustration followed by fleeting moments of eureka. When we briefly understood something, we would spin our chairs toward each other and try to explain it in plain English, which inevitably led to questions and then, “okay… hmm… I’m not quite sure… let me think about that.” Questions begot questions.

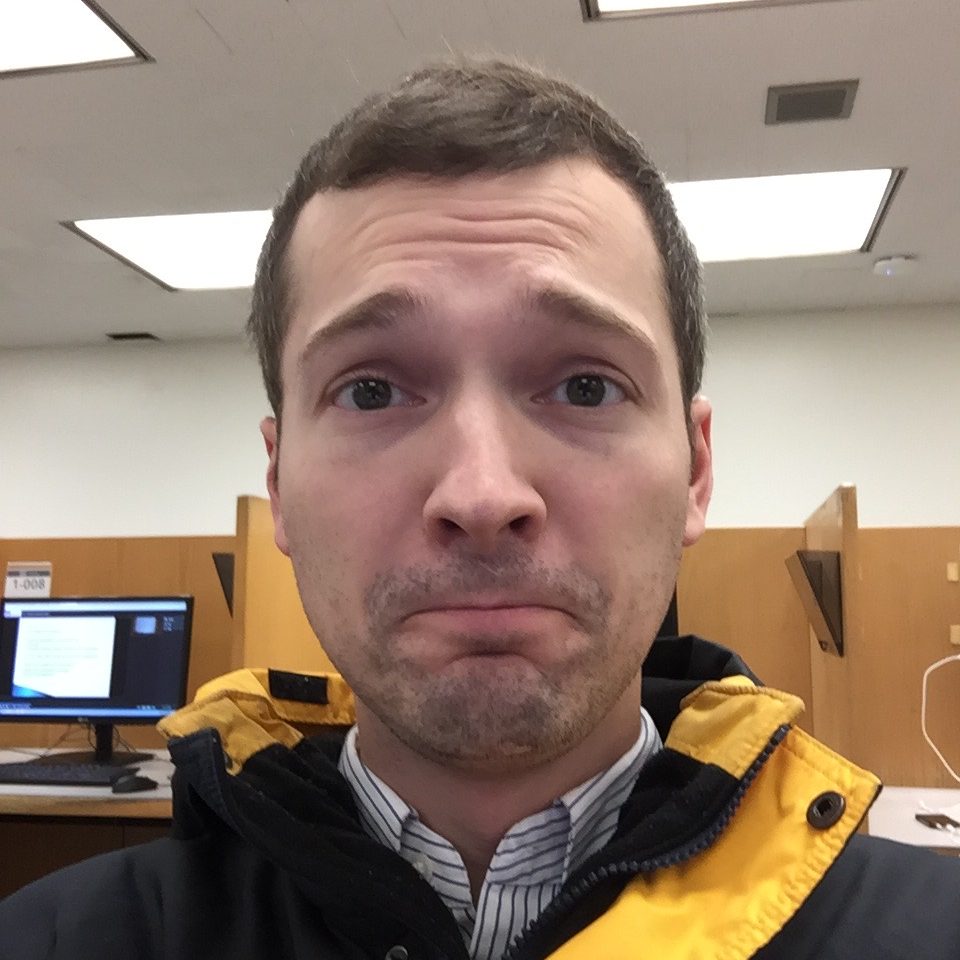

I looked through old photos to see if I could find one from those days in the library. This is the only one I could find. My face says it all. Ha!

Last fall, I remember sharing with my doctoral students in Advanced Mixed Methods Research that learning research methods and completing a dissertation involves going out into the desert. [The featured image above is of my brother Louie and me journeying in a Colorado desert in 1996.] The doctoral journey can be lonely and frustrating and terribly slow. But that may be the ONLY way to deeply understand research methods and complete a dissertation. It is a (mostly) self-directed process that involves dealing with ambiguity and questions at every turn, which the learner is responsible for exploring.

As professors, we do our students a disservice by valuing expedient performance instead of creating environments where slow struggle can occur. Of course, part of the problem is that students have become accustomed to a type of learning built around “just tell me what to do and how exactly to do it and I’ll do it.” For more on this, check out William Deresiewicz’s 2015 book Excellent Sheep: The Miseducation of the American Elite and the Way to a Meaningful Life. This means that creating an environment for good struggle is not often warmly welcomed. It’s mistaken as poor quality of instruction or dismissed as unnecessarily difficult. For understandable reasons, students want quick learning, high grades, and some kind of extrinsic recognition like a degree, credential, or certificate they can post on LinkedIn. I don’t blame them. Students are busy, and so much of our society is built around résumé-type “learning.”

But a good parallel is athletics. If I were a track and field coach, would I be doing my athletes any good by making practice quick and easy? Teachers, like coaches, are responsible for creating assignments that will kindly push our students in meaningful ways, but no one can run the race for us. I’m grateful I did track in high school and continued a habit of training for long-distance athletic events. The parallel with daily training towards a seemingly impossible goal has been helpful to me. [I ran a 50-mile ultramarathon the same month I completed my comprehensive exams.] This is a tricky line to walk with students, though, and I’m working on becoming a better teacher/advisor.

In my own life and work, the first thing I do in my office on many mornings is read a journal article or book chapter out loud while taking notes. It’s hard to do when email and to-do lists are shouting at me, but reading out loud slows me down and helps me to think as I read. My favorite pen (a Pilot G-2, 0.38) allows me to write down little notes that aid my cogitation. Reading out loud is a slow process, but it’s one of the core practices I would credit with my success as a learner and scholar. Slow > Fast.

Funnily enough, common advice for ultramarathon racing is “start slow, and then slow down.” The same probably applies to deep learning, too.

Onward.

Great article. I really enjoyed it. It’s funny how that works with learning. Always ups and downs, just have to stick with it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Marek!

LikeLike